A Wedding Journey through Karbi Anglong

I’m back from the misty hills of Assam with a heart full of stories that feel etched into my bones. If you’ve ever chased a friend’s wedding across winding roads—and stumbled into a cultural tapestry that rewires your ideas of love, community, and even the quiet magic of a good bike ride—buckle up. This one’s for you.

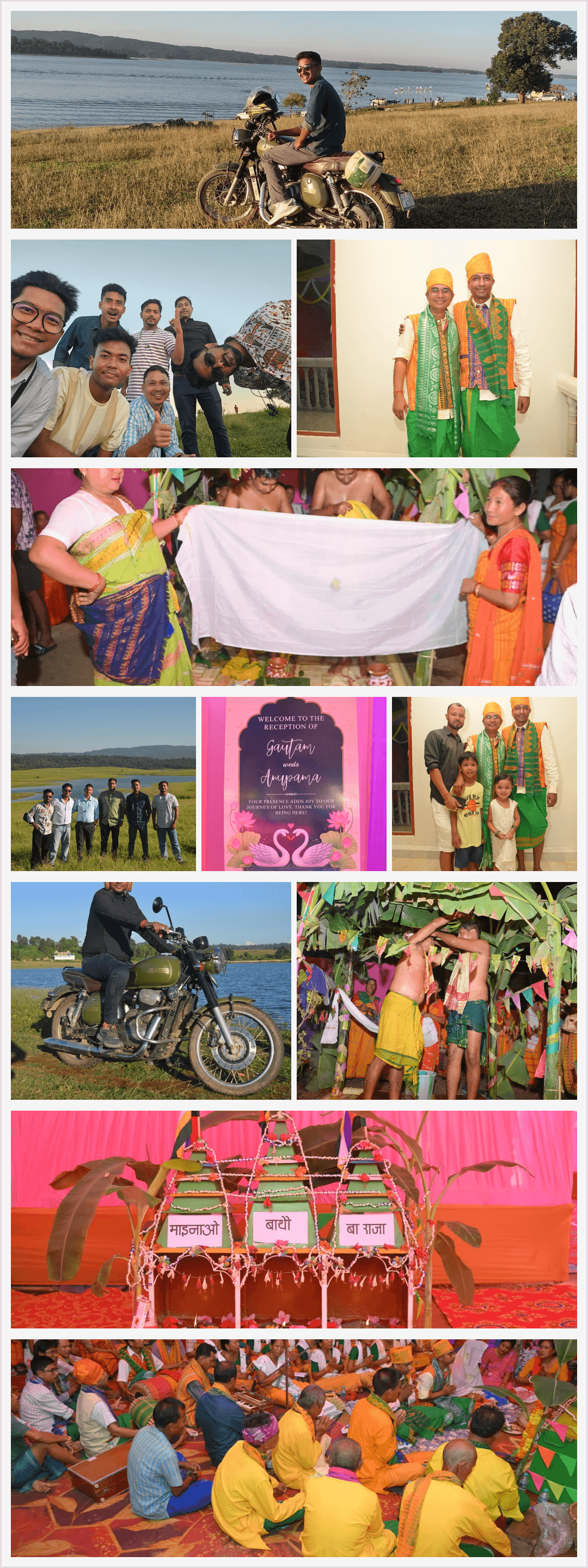

My friend Gautam was tying the knot in true Karbi style. The twist? I got groom’s‑view seats to not one, but two traditional weddings—Karbi and Bodo—as the couple honored both of their tribes’ rituals. It felt like the universe had enrolled me in a crash course on living traditions, and I was there for every vibrant, earthy detail.

I was asked to become the groom’s “hoki” (Sakhi). To do so, we went through rituals and took oaths before the earth, sun, water, and the community—promising to care for each other in hard times. It felt like we’d sanctified our friendship. I was handed an umbrella to shield the groom from rice grains as we entered the bride’s home. I laughed it off—until we arrived. Outside, 40–50 young men were cracking jokes, and the air hummed with the kind of mischief that belongs to weddings. The elders stepped in, negotiated, and we made our entry. I held the umbrella like Captain America’s shield, grains pinging off the fabric as we threaded through the crowd to protect our eyes. One woman still managed to sneak her hand from below and shower us with rice. In minutes, the joyous ambush was over, but it left a grin I couldn’t shake.

The Karbi wedding, Adam Asar, began with elders leaning in to whisper words that felt like charms against the evil eye. No Karbi celebration starts without rice beer; we exchanged bongkrok and shared food that tasted like it had stories of its own. The next day, the Bodo ceremony—Batho Juri—took place. The Bodo follow Bathouism; “Ba‑thou” comes from the Bodo words ba (five) and thou (deep philosophical thought). The five principles of creation are Bar (air), Ha (earth), Dwi (water), Or (fire), and Okhrang (sky/ether). A ritual space with three deities was prepared: in the center, Bathou, the supreme god; Mainao, goddess of wealth and crops; and Ba Raja, a prominent household god. I loved how the sacred sat so comfortably in the everyday.

Because there were two weddings, Gautam and I received haldi and oil baths from relatives on two days. We sat on a floor made from banana trunks while the women sang wedding songs—voices warm and steady, the kind that settle you. The first day felt puzzling; by the second, we knew the drill. We were washed, our faces covered, and guided to our rooms. A relative carried each of us on his back. I felt terrible for the one who lifted me—I’ve gained some solid weight lately—and we all laughed. Our paternal uncles and aunts dressed us. The weddings flowed into the reception like a river that knew its banks.

A thread ran through everything: sustainability. Banana plants and biodegradable materials were everywhere—nothing wasted, everything repurposed. To an outsider it might read like a carefully funded research project from a top university or an EU guideline. Here, it’s simply how things are done—and have been, for generations.

We slipped away to Umrangso the next day. I hopped on a bike with the cousin Monu, an expert rider. I can handle a bike, but I’m not exactly hands‑on. We reached around 3:30, the sun easing off, a soft gold settling over the meadows. The wind smelled green and a little sweet. We waited for the sunset, took a ton of photos, and promised ourselves a camping trip next time. On the way back, a few road issues reminded us of the importance of proper biking gear. Still, the ride was splendid. I reached home yesterday and, fortunately, missed the Diwali and Chhath Puja rush. Until May this year I’d been practicing neti neti—peeling away what isn’t essential. Wu‑Wei is working for me so far.

I didn’t get much one-on-one time with Gautam, but I met a cast of unforgettable people. A dancer who loves nothing but dance—he made me forget the world and just move. A tabla-and-flute musician by day and a master rice-beer brewer by night. Monu, the biker who pulled off that 2 km ride, is as trustworthy as they come—best wishes to him. My paternal uncle (Khura), whose name I’ve embarrassingly forgotten, is a born improviser who can finish any task with whatever’s at hand. Gautam’s brother-in-law is an open-hearted host who shares his stories and gets what we’re going through. I also reconnected with friends from my last trip—Gautam’s circle and his brother Digbijoy’s crew. And Digbijoy, a Fine Arts graduate, is pure fun to be around—the chill guy everyone wants nearby.

For five months I was deep into learning and building in AI. I’m glad I stepped away from the FOMO to be with real people again—to feel the full spectrum of being human and humane. Assam felt inclusive and hospitable; its people are passionate. Every day there, someone was talking about the loss of Zubeen Da. Assam will keep creating musical legends, and his loss is irreplaceable. Moments like these make me think about how we hold our artists—how demand, adoration, and pressure sometimes blur into one. If there’s truth to be found in any controversy, I hope it’s found with care and justice. More than anything, I hope we resist the culture of greed that forgets the human being at the center.

Now I’m back at base, easing into AI again. Moving places always hurts; I miss people, and sometimes I avoid trips just to dodge that ache. Maybe the best thing is to talk about it. Everyone feels this pull. I’m so damn glad I made it to that wedding. It wasn’t just a celebration; it was a recalibration.

“Every time my surroundings change, I feel enormous sadness. It’s not greater when I leave a place tied to memories, grief, or happiness. It’s the change itself that unsettles me, just as liquid in a jar turns cloudy when you shake it.” —Italo Svevo

️

️ ️

️ ️

️